https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdinand_Keller_(painter)

The painting below is from Ferdinand Keller and I realized that his paintings.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One_Thousand_and_One_Nights

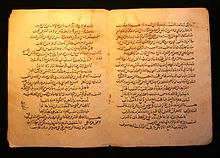

One Thousand and One Nights (

Arabic:

كِتَاب أَلْف لَيْلَة وَلَيْلَة

kitāb ʾalf layla wa-layla) is a collection of

Middle Eastern,

West Asian and

South Asian stories and folk tales compiled in Arabic during the

Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the

Arabian Nights, from the first English language edition (1706), which rendered the title as

The Arabian Nights' Entertainment.

[1]

The work was collected over many centuries by various authors, translators, and scholars across West, Central, and South Asia and North Africa. The tales themselves trace their roots back to ancient and medieval

Arabic,

Persian,

Mesopotamian,

Indian, and

Egyptian folklore and literature. In particular, many tales were originally folk stories from the

Caliphate era, while others, especially the frame story, are most probably drawn from the

Pahlavi Persian work Hazār Afsān (

Persian:

هزار افسان, lit.

A Thousand Tales) which in turn relied partly on Indian elements.

[2]

What is common throughout all the editions of the

Nights is the initial

frame story of the ruler

Shahryār (from

Persian:

شهريار, meaning "king" or "sovereign") and his wife

Scheherazade (from

Persian:

شهرزاد, possibly meaning "of noble lineage"

[3]) and the

framing device incorporated throughout the tales themselves. The stories proceed from this original tale; some are framed within other tales, while others begin and end of their own accord. Some editions contain only a few hundred nights, while others include 1,001 or more. The bulk of the text is in prose, although verse is occasionally used for songs and riddles and to express heightened emotion. Most of the poems are single couplets or quatrains, although some are longer.

The main

frame story concerns Shahryar, whom the narrator calls a "

Sasanian king" ruling in "India and China".

[5] He is shocked to discover that his brother's wife is unfaithful; discovering his own wife's infidelity has been even more flagrant, he has her executed: but in his bitterness and grief decides that all women are the same. Shahryar begins to marry a succession of virgins only to execute each one the next morning, before she has a chance to dishonour him. Eventually the

vizier, whose duty it is to provide them, cannot find any more virgins.

Scheherazade, the vizier's daughter, offers herself as the next bride and her father reluctantly agrees. On the night of their marriage, Scheherazade begins to tell the king a tale, but does not end it. The king, curious about how the story ends, is thus forced to postpone her execution in order to hear the conclusion. The next night, as soon as she finishes the tale, she begins (and

only begins) a new one, and the king, eager to hear the conclusion, postpones her execution once again. So it goes on for 1,001 nights.

The tales vary widely: they include historical tales, love stories, tragedies, comedies, poems,

burlesques and various forms of

erotica. Numerous stories depict

jinns,

ghouls,

apes,

[6] sorcerers, magicians, and legendary places, which are often intermingled with real people and geography, not always rationally; common

protagonists include the historical

Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid, his

Grand Vizier,

Jafar al-Barmaki, and the famous poet

Abu Nuwas, despite the fact that these figures lived some 200 years after the fall of the

Sassanid Empire in which the frame tale of Scheherazade is set. Sometimes a character in Scheherazade's tale will begin telling other characters a story of his own, and that story may have another one told within it, resulting in a richly layered narrative texture.

The different versions have different individually detailed endings (in some Scheherazade asks for a pardon, in some the king sees their children and decides not to execute his wife, in some other things happen that make the king distracted) but they all end with the king giving his wife a pardon and sparing her life.

The narrator's standards for what constitutes a

cliffhanger seem broader than in modern literature. While in many cases a story is cut off with the hero in danger of losing his life or another kind of deep trouble, in some parts of the full text Scheherazade stops her narration in the middle of an exposition of abstract philosophical principles or complex points of

Islamic philosophy, and in one case during a detailed description of

human anatomy according to

Galen—and in all these cases turns out to be justified in her belief that the king's curiosity about the sequel would buy her another day of life.

.

.

.

.

I let myself suspend through the hidden realms of me..

I let myself suspend through the hidden realms of me..